I’m a big turn-based strategy game player, and a lot of the ideas behind Star Dynasties came from such games, including the way the player typically interacts with the game.

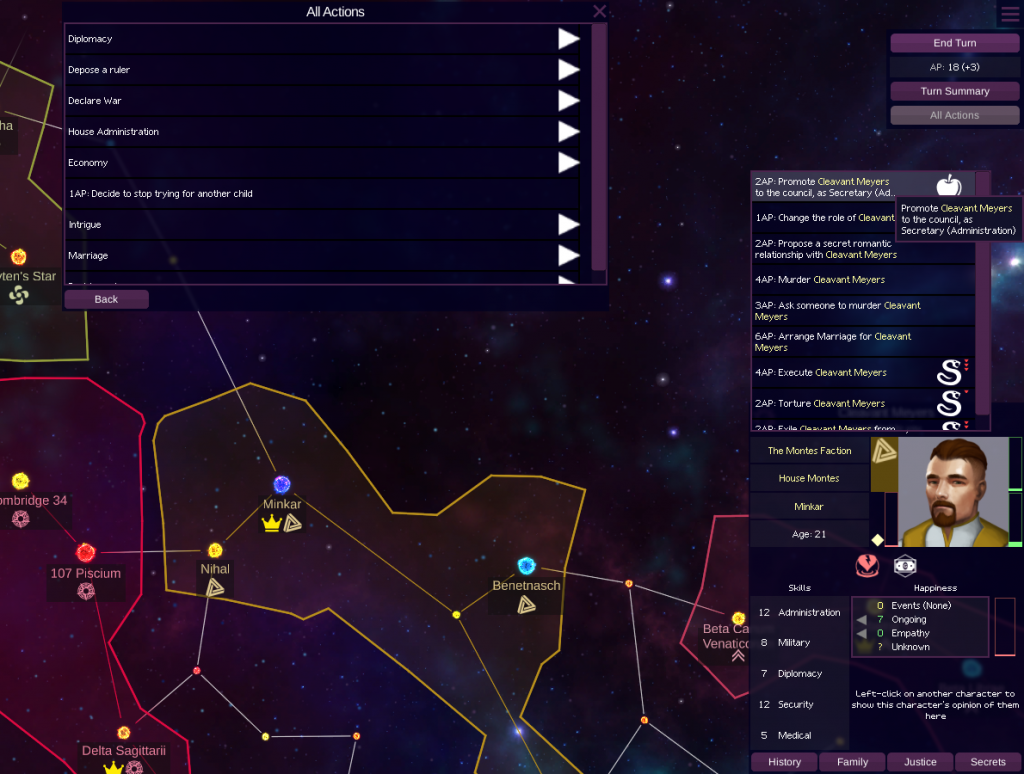

You see a map of the galaxy, which you can explore to understand your situation and work out what are the most important issues that you need to address, or what the next steps are to achieve your longer-term strategy of succeeding in the game.

To interact with the game, you have access to a global list of all the actions you can take, or you can click on specific entities in the galaxy (such as a character) and see a list of the specific actions you can take that are context-specific to that character. Your character has a set of action points that limits how many actions can be completed in one turn, and after you consume them (or when you feel there is no further good action to take) you choose to End the Turn. I call this more typical way to play the game Strategy Mode.

Another Way to Play

As I described in the post about the game’s vision, Star Dynasties is designed to focus more on the human dramas of a feudal society in space, rather than the micromanagement of empire building or military conquest. A consequence of this focus is that actions are similar to events in a narrative rather than task instructions, e.g. “Find a marriage partner for John” as opposed to “Move Unit X from Sol to Alpha Centauri”.

As I explored different ways to structure the UI, particularly trying to deal with early feedback that there was a steep learning curve to pick up the concepts of the game, I realized that the nature of the game’s action list allows the possibility of a seperate and complementary choose-your-own-adventure interface to playing the game, which I call Story Mode.

Instead of giving you the full set of actions to explore, the game presents you with 3 possible choices which the AI calculates as the most realistic actions that your character would take next, based on their personality traits, and current situation (with the occasional curveball thrown in).

You select one action, and take any further decisions required by the process flow of that action (e.g. marriage action asks you to choose a marriage partner). After the action is fully resolved, you are presented with another decision between three choices. At any time, you can elect not to take any of the actions offered, in which case this is equivalent to ending your turn. In most cases, however, multiple actions will be attractive and you will have to decide what to focus on, knowing that you may not get the same opportunities again as the simulation changes the world state.

Furthermore, the UI proactively fetches the information that is most relevant to each decision. For example, if you are choosing between suitors in a marriage, as you mouse over each one, the UI will bring up that character’s details, their family, and their political house. Lastly, decisions with lots of alternatives are simplified down to the subset that the AI thinks are the best. In the marriage suitors example, the AI will shrink the alternatives down to the 3 that it thinks are a good match.

It’s important to note that beneath the changes to the UI, it is the exact same game and world simulation. That said, the interaction mode you choose leads to two very different experiences.

Contrasting the two Modes

In Story Mode, the game feels considerably more like a narrative in which you roleplay a character and guide their actions. Because the game does more of the legwork in filtering actions and presenting you with the information you need to take a good decision, it’s a more streamlined experience that allows you to focus on the story that’s unfolding. It’s also easier to pick up when you’re new to the game, or if you don’t have a lot of time to devote to it.

In Strategy Mode, your ability to trigger actions that may be wildly out of character (such as declaring war on your best friend) gives you the freedom to choose how much you want to roleplay your character, or perhaps play the game in order to conquer the galaxy or build a powerful dynasty across the generations. It can also be more satisfying if you enjoy exploring the world and it’s detail at your own pace.

I believe that most players will be naturally drawn to one mode or another, although not necessarily the one they expect – despite my background as a strategy game player I’ve found myself thoroughly enjoying Story Mode.

There is of course a cost, and a design risk, in implementing two interaction modes instead of one. However, I am hoping that this is outweighed by the potential reward of engaging two complementary audiences.

Want to Comment?

Please share your feedback about Strategy Mode / Story Mode and join in other discussions on the Star Dynasties reddit